Last Updated on May 7, 2025

Is Russia currently on the gold standard?

Despite a lot of speculation to the contrary, the answer is no.

In early 2022, in an attempt to defend the value of the rouble, the Russian Central Bank said that it would buy gold at 5000 roubles per gram.

However all this meant was that the bank would buy gold with paper. It made no commitment to redeem paper for gold. For a gold standard to be put into effect a central bank must be prepared to buy and sell gold at a fixed price.

You can read more about current developments in my article on the Moscow World Standard.

But Russia was in fact on a type of gold standard back in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Russia adopted the gold standard in 1897 and abandoned it with the outbreak of the Great War in 1914.

The classical gold standard had emerged in the 1870s as the world’s powers, led by the USA and Germany abandoned bimetallism and demonetised silver.

Russia was a little late to make the formal switch to gold, but eventually did so two decades after the other major powers. The move to the gold standard stabilised the Russian currency, incentivised foreign investment and sped up Russia’s development into a modern industrial power.

The era of the classical gold standard is widely regarded as humanity’s most glorious monetary era to date. The famous monetary system lasted until the outbreak of war in 1914 when the European powers, including Russia, removed their currencies from gold in order to print money to finance the Great War.

The economies of most World War One belligerents recovered somewhat in the post-war environment. However, in Russia, the abandonment of the gold standard had a much more devastating effect and she never really recovered.

Two revolutions in 1917 resulted in the Tsar abdicated and then the Bolsheviks seizing power. And as if the Great War was not enough, a civil war raged until 1922 leaving the economy and society in tatters.

Russia experienced hyperinflation as the Bolsheviks who sought to impose their fantasy of a moneyless society on the country. While they eventually abandoned that crazy idea, the Bolsheviks imposed hardship and suffering on Russia and the Soviet Union for many decades until the fall of communism in 1991.

This is the story of how Russia adopted and then abandoned the gold standard and the lessons we can learn from it.

A Brief History Of The Russian Empire’s Currency From 1768

Russia gained the status of a great power under Catherine the Great who reigned from 1762-1796.

This status was accorded because of the country’s military expansionism. The problem was that military expansion needed financing.

When Catherine assumed the throne Russia was on a nominal silver standard but there was little of the metal in circulation. So she did what many states have done, past and present, and decided to finance her military adventures with paper.

In 1768 the first paper money was first introduced into Russia, the rouble-assignat.

Two banks, one in St Petersburg and the other in Moscow, were authorised to issue this currency.

By 1786, 50 million rouble-assignats had been issued. This first issue was quite stable because they were backed by the state’s gold reserve.

However, like all governments, the temptation to increase the supply of paper money beyond the gold reserve was too much to resist. Therefore, in 1786, the tie to gold was severed and the currency in circulation doubled to 100 million units.

The two banks authorised to issue paper money soon merged to become the State Assignation Bank.

By 1796, the year of Catherine’s death, the currency in circulation had swelled to 157 million units.

By the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 that figure was over 800 million.

Measured against silver, the rouble-assignat had lost nearly 80% of its value.

At that point the government decided that something needed to be done to improve the monetary situation.

In 1817 it was decreed that no new rouble-assignats could be printed. The government then began a contraction of the currency supply.

It took a long time but eventually the restraint on issuing new currency and the success of the currency contraction culminated in the return to a precious metal backed currency.

In 1843, the credit-rouble was established. Despite the dodgy fiat sounding name it brought about confidence and stability as it was freely redeemable in silver.

Unfortunately, the Crimean War led to convertibility being suspended again in 1857. The government had doubled the supply of paper notes since the creation of the new currency and so this led to citizens were doing the wise thing and start converting devalued paper into hard money.

But with the silver reserves dwindling and not enough silver to redeem the full issue of paper currency, the government suspended convertibility.

It was in this environment that the decision was made to create a state bank. This was authorised by Alexander II in 1860 and went into operation in 1862.

It wasn’t a central bank in the modern sense. It also operated as a commercial bank and was under the supervision of the Ministry of Finance.

The creation of the state bank was not able to resolve the problem of the poor state of the currency. Russia consumed more than she produced and made the difference up in loans. This was unsustainable in the long term.

The Russian Empire Moves Towards A Gold Standard

Global developments in the early 1870s began a shift away from bimetallism and onto the gold standard.

Notable shifts in policy happened in Germany and the USA. Both countries joined Britain as gold standard nations.

Despite the disastrous periods of paper money expansion, and the inconvertible currency, Russia was still on the silver standard.

From the 1870s, the value of silver fell around the world due to the demonetisation in the USA, Germany and elsewhere. This was a major problem for silver standard nations.

The Russian government, needing to remedy the problem of a wildly fluctuating and volatile currency, decided that she too would begin the move to gold. Although these moves began in the 1870s, it would take more than two decades to complete the process.

The first move towards gold happened in 1876 when a government decree ordered that customs dues be paid in gold. Any customs dues paid in paper money had to be doubled. This effectively gave the notes a 50% devaluation against gold.

From 1881 the value of loans in Russia was commonly stated in terms of gold.

Sergei Witte, Russia’s famous statesman, assumed the office of Minister of Finance in 1892. and he began preparations for a move to a gold standard.

One of his first steps taken was in 1893. He ended the coinage of silver and prohibited the importation of silver into the country.

Another decree in 1893 put a tariff on the import and export of large sums of paper roubles. It was thought that currency speculation in Berlin was responsible for a large decree of the fluctuation of the rouble, so this move was designed to reduce the speculation and thus the volatility. Currency speculation within Russia was also forbidden.

In 1895 a law was passed that allowed all contractual obligations to be expressed in terms of gold.

While all these preliminary steps were being taken, Witte continued to build the Russian government’s hoard of gold, including taking out foreign loans and using the proceeds to purchase more gold.

In August 1896 the price of the paper rouble was fixed to gold. The exchange rate was 1 paper rouble to 66.66 gold kopecks.

(The Kopeck was a Russian unit of account similar to a cent. 100 kopecks were equal to 1 rouble. This means one gold rouble would be equivalent to 1.5 paper roubles.)

Meanwhile enough gold had been accumulated to ensure that full convertibility between paper money and gold could be achieved. It is significant to note that Russia’s gold reserves, at this point, were larger than both France and Britain’s.

In January 1897, the gold standard took effect. Nicholas II himself presided over a special session of the State Council. The emperor’s decree instituted a new gold coinage which became the monetary standard of the nation.

This 1897 decree also amended the 1896 ratio between gold and paper and restored parity between the two. One paper rouble was equal to one gold rouble. This was achieved by lowering gold content in the gold rouble.

Olga Crisp explains why this devaluation took place:

“This procedure was necessary because the Council would have agreed to the convertibility of the paper rouble only on the basis of parity with gold, while Witte realized that the raising of the paper rouble rate to par was hardly practicable, as it could be achieved only in one of three ways: by gradually strengthening the paper rouble; by substantially increasing the gold reserve; or by reducing the volume of paper roubles in circulation-all of them impossible or dangerous.”

Since strengthening the paper currency was out of the question, devaluing the gold rouble by reducing it’s gold content was the path that Witte chose. The old imperial 10 rouble gold coin was replaced by a coin with the same weight and purity but was stamped with 15 roubles instead.

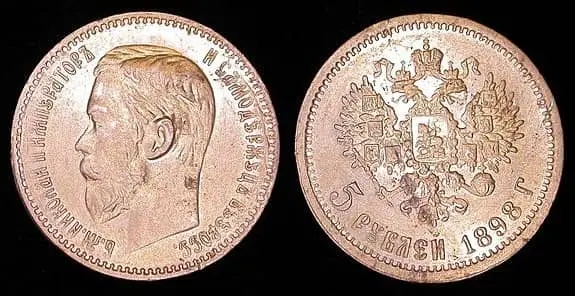

Another prominent coin to be minted in this period of Russian history was the 5 rouble gold coin. This coin is still quite famous and well known among numismatists.

The Implementation of the Russian Gold Standard

There were a diverse range of opinions in Russia on whether the gold standard would succeed. Unsurprisingly, there were those who thought it would be doomed to failure.

They predicted that the gold would be hoarded or end up abroad. They thought that Gresham’s law would remove it from circulation and the government would be forced to end free convertibility.

Some argued in favour of bimetallism or a paper standard. Others made the case against the devaluation.

Even the French Premier even tried to convince the Tsar that adopting the gold standard was a bad idea.

Nevertheless the reform proceeded in spite of the opposition. This is something Witte attributes entirely to Nicholas II:

“In the end I had only one force behind me, but it was a power stronger than all the rest – that was the confidence of the emperor. And therefore I repeat that Russia owes its metallic gold currency exclusively to Emperor Nicholas II.”

Despite the critics, the implementation of the gold standard happened without incident.

Sergei Oldenberg describes the process:

“The monetary reform entered Russian life without fanfare and, contrary to the warnings of its opponents, without creating any tremors in the economy. For two years already the rate had stayed stable. The speculation in rubles had ceased…Gold did not flow abroad, nor was any significant amount of it hidden away. Russia meanwhile stabilised its international financial position by painlessly moving on the gold standard, which by then most of the great powers had adopted.”

The Russian gold standard required a 50% reserve of gold to be held against the first 600,000 roubles. And a 100% reserve to be held against all roubles issued in excess of 600,000.

No other bank was authorised to issue notes. This gave the state bank a monopoly on the issue of currency.

Notes were fully redeemable in gold.

One of Russia’s problems in maintaining a stable currency, since the time of Catherine the Great, had been the drain on her finances caused by war.

This is something that Witte was well aware of.

Olga Crisp explains:

“In his report to the Emperor in January 1898…he stresses the connexion between foreign policy and state finance and issues a warning against ‘dangerous fancies’ and advises the pursuit of a peaceful foreign policy ‘alien to aggressive aspirations’.’ Furthermore, on the short-term view he was conscious of the dangers to his monetary policy inherent in heavy military expenditure which not only added to the budgetary burden but also represented a drain on reserves of foreign exchange.”

The 1890s and early 1900s were relatively peaceful times for Russia. They proved to be a good time for monetary reform and industrial development. Russia would not go to war again until 1904 when she came into conflict with Japan.

Witte had timed his move well.

One of the key reasons behind Russia’s desire to adopt the gold standard was to stabilise the currency in order to encourage foreign investment.

Russia was far behind the other European powers in terms of industrial development. She knew she needed to catch up.

Capital was necessary but that capital needed to be attracted.

Alexander Nove explains:

“The progress of Russian industrialization suffered from relative shortage of capital, as well as from a poorly developed banking system and a generally low standard of commercial morality. The traditional Muscovite merchants, rich and uneducated, were far from being the prototypes of a modern commercial capitalism. The situation changed towards the end of the nineteenth century, and particularly during the rapid industrialization which characterized the nineties. There was a marked growth of both Russian and foreign capital, and an equal improvement in the banking system. Russian entrepreneurs of a modern type began more and more to emerge. Under cover of the protective tariff of 1891, and with the establishment of a stabilized rouble based on the gold standard, foreign capital received every encouragement.”

In this regard Witte was successful as well. This is partly because foreign capital was more prepared to invest in Russia in a stable monetary environment, but also because the adoption of the gold standard improved Russia’s access to Western capital markets.

Gold is not a national currency, it is the world’s money and it is neutral. When people use a neutral international currency, capital and commerce flow and economies flourish.

Interestingly, some have criticised Russia’s adoption of the gold standard. They argue that the cost to acquire gold reserves exceeded any benefit from going onto the gold standard.

This is similar to the argument made by Milton Friedman. He advocated for a paper standard over gold because of the cost involved in gold mining. It is also similar to the arguments made against Bitcoin, that it is too energy intensive and that cost should mean we don’t use it as money.

Ludwig von Mises’ argument in response to this criticism is that yes, there is a resource cost to having a hard money standard. But that cost is worth paying for the benefits to society and the economy that accrue from the adoption of a hard money standard.

Specifically regarding the Russian gold standard, this is the conclusion that Paul Gregory reached as well. He explains:

“The major cost of achieving convertibility was that two-thirds of official borrowing abroad between 1885 and 1897 was used to acquire gold reserves, but the ensuing growth benefits which are estimated far outweigh these costs.”

So it is safe to conclude that Russia’s adoption of the gold standard was a success, which should come as no surprise to those who understand the advantages of hard money.

The Abandonment of the Gold Standard in Russia

At the outbreak of World War One, Russia, like the other European powers suspended convertibility of paper notes to gold.

To meet the large cost of war on a gold standard would have meant raising taxes and putting the maximum financial pain on the population right at the start.

While they did raise taxes and borrow as well, it was much easier for governments to finance much of the war cost through inflation and pass the cost on to the future.

Vincent Barnett explains the Keynesian philosophy of war financing:

“The issue of paper currency and the resulting price inflation had been a preferred manner of raising (some percentage of) wartime revenue, provided that certain other conditions were met. This was because governments had to find a way of reducing the purchasing capacity of the general population and of transferring this diverted means to the war effort, in order to successfully pay for the extra expenses of the military campaign. Allowing prices to rise more than money wages, so that real wages were reduced, was an expedient method of diverting economic capacity from civilian use to the war effort.”

It is estimated that around 60% of the Russian government’s war expenditure was met by borrowing and around 30% was met by currency creation.

The supply of money in Russia grew more than 11 times from the outbreak of war in 1914 to the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

From the government’s point of view, suspension of convertibility into gold was necessary, otherwise the printing of currency would force the public to demand redemption in gold and cripple the government’s war effort.

Writing in 1924, Harvey Fisk argues that the Russian authorities understood the danger but felt they had little choice.

“Knowing the evil consequences of repeated and large issues of paper money, Russian economists and the authorities were none too anxious to inflate the currency, but they had to deal with a population little used to bonds and other securities and which preferred to receive wages and keep savings in paper which they could understand. This, in a way, explains the great increase in bank notes during the war.”

The wartime situation in Russia was then made particularly bad by peasants “seceding” from the rest of the economy by moving to more semi-subsistence agriculture.

They would prefer to consume or hoard agricultural produce rather than sell it for a rapidly depreciating paper currency. The paper currency that peasants did have was then hoarded and kept outside the banking system.

The inflation and hoarding of foodstuffs by peasants meant the cost to the state of feeding the army skyrocketed, leading to the imposition of price controls, further inflaming the situation.

The combination of currency creation, declining production and price controls led to an explosive rise in prices. Gresham’s law forced gold and silver out of circulation.

The Tsar abdicated in the February Revolution of 1917 but the economic and monetary crisis continued under the new Provisional Government before the Bolsheviks took power in October 1917. They crazily attempted to solve the problem by implementing a moneyless society.

The Bolsheviks’ policies made the bad situation even worse and tipped the country into hyperinflation.

A degree of monetary stability was only restored when Lenin decided to ban currency printing to cover budget deficits and moved to partially back the Soviet currency with gold as well as issue silver and copper coins.

Sadly for Russia the nightmare was not over as they then had to endure Stalin and several decades of more socialism.

Lessons From The Russian Empire’s Adoption of the Gold Standard

1. A Paper Currency Can Lose Significant Value But Life Goes On

Between 1768 and 1815 the rouble-assignat, the paper currency of Catherine the Great, lost over 80% of its value against silver.

It took another 82 years before Russia went on the gold standard. In that time life went on and the economy developed. Yes, life was tough in Russia in those days and there was significant economic hardship.

But a collapse in the value of the currency was not the end of the world.

These days you will see plenty of memes and charts about how the US dollar has lost over 90% of its value since the advent of the Federal Reserve System.

That is true and it is a tragedy with a high social cost that has caused unnecessary pain for generations of people both in America and around the world.

But life goes on and the American and global economies have moved forward in leaps and bounds despite the devaluation in the dollar.

As Warren Buffet notes:

“Over my lifetime, the US dollar has lost over ninety percent of its purchasing power. Yet even after adjusting for that inflation, the net output of our economy has grown by over twenty times – over 2000%”

Your lifetime is short. It certainly can be shorter than the lifespan of a failing currency. As an investor you need to acknowledge the situation and plan accordingly, but as a person you need to stop and smell the roses even in difficult economic circumstances.

So yes, the US dollar is rapidly collapsing in value. Either the authorities will rein in their destructive behaviour and slow the collapse. Or they will issue a new fiat currency. Or we will move to some kind of hard money standard.

Pay attention and stay vigilant. But don’t worry too much.

As Jim Rickards often says, we won’t be eating canned foods and living in caves.

2. It Can Take a Long Time to Restore or Implement a Hard Money Standard

Hard money advocates often wish that governments would just implement hard money at the stroke of a pen tomorrow.

Or that governments would just abandon fiat currency entirely and let the market set the hard money standard.

This is just wishful thinking.

Governments enjoy their monetary monopoly and they are never too keen to relinquish it. It is their sovereign right to set the monetary standard.

While I believe a smart state would step back and let the market decide the monetary system, if you are a realist and have studied history you know they rarely do so.

If, for whatever reason, a state comes to its senses and decides to implement a hard money standard, it isn’t an overnight process.

It can take time, sometimes a long time, depending on the mechanism by which it is implemented.

In 1817, two years after Napoleon was defeated, Russia ceased printing new paper money and started moving towards a hard money standard. But it took them 26 years to get there, finally returning to a metallic standard in 1843.

The 1897 adoption of the gold standard has its genesis in the 1876 decision to collect customs duties in gold. It took 21 years for the government to build the mechanism, the gold reserve and the courage to adopt the gold standard.

Plenty of moves are afoot in the modern day that suggest nations are preparing themselves for a new monetary system and possibly a gold based one. The includes the Russian development of the Moscow World Standard.

Things will very likely change in the global monetary system in the 21st century, but we don’t know when and as investors we have no idea how long we might be waiting.

But just because governments might drag their feet doesn’t mean that you have to. You can put yourself on your own hard money standard by converting some of your fiat to gold or Bitcoin today.

Read More: How To Invest In Gold For Beginners

3. There Are Several Ways to Implement a Gold Standard.

After deciding that Russia would only adopt gold when the gold rouble and paper rouble were at a par, Sergei Witte had four options available to him.

He could have strengthened the paper rouble, increased the gold reserve, contracted the supply of paper roubles or reduced the metallic content of the gold coins.

He chose the latter because he felt that all other alternatives would have had an adverse affect on the economy either by increasing the value of debts or causing significant price increases.

We’ve seen what happened in the 1920s when the British returned to the gold standard at the wrong price, without accounting for their massive wartime currency creation. It caused the Great Depression.

Things can go badly wrong if the adoption of a hard money standard is not done correctly and, to Witte’s credit, it seems that he got it right.

Adopting a hard money standard while unwinding the harms caused by massive printing of fiat but with the minimum amount of economic and social disruption is incredibly difficult and is a great balancing act.

Of course we want a hard money standard but we shouldn’t kid ourselves that it will be an entirely simple or painless process.

4. Detractors Will Always Exist

It’s no great secret to any hard money person than we are in the minority in the 21st century.

But even when the world’s major powers were on gold and in the middle of the classical gold standard, Russia still had those who felt going onto gold was a mistake.

If anything, you would assume that the monetary climate in the world at the time should have made the argument a slam dunk in favour of gold.

Yet many preferred bimetallism. This was also an argument of many in the United States at a similar time, so I guess it’s unsurprising that it existed in Russia also.

Many were also critical of the devaluation of the metallic content in the coins, which is a fair and understandable criticism.

What seems crazy though is that there were some who wanted a paper standard. When the world is on gold and you have the opportunity to go onto gold, you want to stay on paper? Seriously!?

But we shouldn’t be surprised. Russia had been on a paper standard for parts of the 19th century. European nations and the United States had gone through paper money experiments. We know the appeal of fiat money is seductive and many policy makers and academics just don’t properly understand the problems it creates.

So if it was politically tough for Witte to get a gold standard across the line in the 1890s it is going to be a lot more difficult for the 21st century hard money supporters to get something across the line today.

The detractors will always be there. But if you have the political capital and the political will, hard money is possible to implement despite the opposition.

5. Abandoning Hard Money Always Leads To Disaster

I can understand why Russian policy makers abandoned the gold standard in World War One. I can understand why all the powers did.

It enabled them to quickly transfer a greater share of their national wealth to the war effort than they would have done through taxation and borrowing alone.

But even if the leaders felt they had no choice, they cannot absolve themselves from the responsibility for what happened next.

No one knew just how devastating the war was going to be when it broke out. But shortages, price rises and the disappearance of metallic money from circulation in accordance with Gresham’s law are entirely predictable results of ending the convertibility to gold and moving to a fiat monetary standard.

It doesn’t matter whether it was deemed a wartime necessity or not, abandoning a hard money standard will always lead to economic hardship. The economic hardship experienced by Russia in World War One was a two fold suffering caused both by the war and the disastrous monetary policy.

Conclusion

Russia joined other major powers by adopting a gold standard in 1897. This was a successful policy decision as she was able to stabilise her currency, attract foreign investment and better connect with Western capital markets.

After switching between paper and silver standards for much of the previous 130 years, a gold standard was a welcome progression forward.

Sadly this monetary era did not last long for Russia. When war broke out in 1914 she abandoned the convertibility of roubles into gold, effectively ending the gold standard.

The economic devastation of war as well as the effects of fiat money destroyed the Russian economy, leading to the February and the Bolshevik Revolutions.

The Bolsheviks wanted to implement a moneyless society and ended up tipping the country into hyperinflation. They somewhat stabilised the economy when Lenin restored hard money out of necessity and put some restraint on the printing press.

The lesson for investors is that a move to hard money can take a long time. In Russia there are two examples of decades long timeframes to move from a paper to a metallic standard.

Governments may or may not get their policy settings or their timing right. You can hope that they will, but since they probably won’t, you have to do what you can to prepare your portfolio and protect yourself accordingly.

Sources

Barnett, Vincent. 2009. “Keynes and the Non-Neutrality of Russian War Finance during World War One.” Europe-Asia Studies 61 (5): 797–812.

Crisp, Olga. 1953. “Russian Financial Policy and the Gold Standard at the End of the Nineteenth Century.” The Economic History Review 6 (2): 156.

Drummond, Ian M. 1976. “The Russian Gold Standard, 1897–1914.” The Journal of Economic History 36 (3): 663–88.

Gregory, Paul R. 1979. “The Russian Balance of Payments, the Gold Standard, and Monetary Policy: A Historical Example of Foreign Capital Movements.” The Journal of Economic History 39 (2): 379–400.

Nove, Alec. 1978. An Economic History of the USSR. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin Books.

Olʹdenburg, S S. 1975. Last Tsar : Nicholas II, His Reign & His Russia. Gulf Breeze, Fla.: Academic International Press.

Owen, Thomas C. 1989. “A Standard Ruble of Account for Russian Bussiness History, 1769–1914: A Note.” The Journal of Economic History 49 (3): 699–706.

Patton, Eugene B. 1911. “The Banking Systems of the Netherlands, Russia and Japan.” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science in the City of New York 1 (2): 442.

Willis, H. Parker. 1897. “Monetary Reform in Russia.” Journal of Political Economy 5 (3): 277–315.

Image Credits

Tsar Nicholas II is in the public domain

Catherine the Great is in the public domain

Rouble-Assignat is in the public domain

Sergei Witte is in the public domain

1897 Gold Rouble is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

1898 Gold Rouble is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

![The Rentenmark: How Hyperinflation Was Solved In Germany [And 6 Lessons You Can Learn From It]](https://www.hardmoneyhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/rentenmark.webp)