Last Updated on April 22, 2025

Key Takeaways

- Introduced in 211 BC, the silver denarius became the primary currency of Rome for nearly 500 years.

- The denarius started with 95% silver content, but emperors gradually reduced its purity to finance wars and state expenses.

- By the 3rd century AD, its silver content had dropped to just 2%, contributing to hyperinflation and loss of public confidence.

- By the late 3rd century AD, extreme debasement led to the replacement of the denarius with new coins (antoninianus, aurelianianus, solidus).

- The debasement of money—whether through reducing silver content or printing excessive fiat currency—leads to inflation and economic instability.

- The history of the denarius serves as a warning about the dangers of monetary manipulation and unsound economic policies.

The Roman denarius was the most important coin of its time and one of the most famous silver coins in history.

Its extensive circulation across the vast reaches of the Roman Empire demonstrates the success of silver as a monetary medium.

According to numismatic history legend Kenneth Harl in his outstanding book Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700:

“The success of Roman currency rested upon its silver coins, which over the centuries often suffered recoinage, debasement, and revaluation that directly affected the supply and use of coins, and thus state expenses, taxes, and prices in the marketplace. Romans employed as their principal coin a modest-sized silver denomination, the denarius, for nearly five centuries.”

You can’t understand the history of Rome without understanding the denarius. Likewise, you can’t understand the history of silver without understanding the denarius.

You also can’t understand both the strength and the limitations of precious metals as money without understanding the role of the denarius in Rome’s rise and the role its debasement played in Rome’s collapse.

Ready? Let’s dive in and start with the meaning of the word, a quick look at the silver content and then get into the history of the denarius.

The Meaning of Denarius

The word denarius literally means 10 asses.

Deni means ten and the aes was a common bronze coin of the early Roman Republic, which the denarius replaced as the monetary standard,

Put deni and aes together and you get denarius.

The plural for denarius is denarii.

The Silver Content of a Roman Denarius

The denarius was first struck in 310BC but it wasn’t until 211BC that it became the dominant monetary unit.

This 211BC denarius had 4.5g of silver and the coin had 95% fineness.

By the end of its life the silver content of the denarius was a mere 2%.

While the Roman denarius is one of the most famous coins in history and one of the reasons behind Ancient Rome’s economic success, it is also a story of debasement, inflation and monetary collapse.

It is a warning for the present day of the folly of abandoning sound money. It is also a warning about the limitations of precious metals as money.

The denarius went through a great debasement throughout its lifetime with the silver content dramatically declining over time.

Read More: What Was The Silver Content of a Denarius?

The Denarius During The Roman Republic

We shall start our chronological tale during the Roman Republic.

In the early years of the Republic bronze coins called aes were used.

As Rome extended her power over the Italian peninsula she incorporated the Campania region, who had been using silver coins styled on the Greek drachma for several hundred years.

The Romans realised that because silver was much more valuable than bronze, it meant it would be much more convenient to settle large transactions with small amounts of silver rather than large amounts of bronze.

So in 310BC the Romans minted the first denarius, modelled on the Campania coinage.

The 310BC denarius was 6.8g of silver at 93.5% fineness.

Rome did not have a local supply of silver and had to rely on conquest to obtain it. Therefore in those early years, bronze coins still circulated as the main form of money.

But then three things happened which catapulted the denarius into dominance.

- The conquest of Magna Graecia, the Greek settlements in southern Italy by 270BC, gave the Romans enough silver to being minting a large enough quantity of denarii to the point where it became a more commonly circulating currency, albeit one of high value.

- The defeat of Carthage and subsequent peace treaty in 241BC obtained a vast quantity of silver in indemnity payments.

- In the Second Punic War (218-201BC), under great financial strain, the Roman Republic undertook the first devaluation and recoinage of silver, either in 213 or 212BC. This was done in order to service the war debt.

The first issues of denarii in 310BC had silver content ranging between 6.3 and 6.8g.

The new Punic War denarius of 211BC had a silver content of 4.5g.

This took place alongside a reorganisation of the denominations of the bronze coins as well as emergency issues of gold coins.

This version of the denarius became the dominant monetary unit for the remainder of the Roman Republic and for the much of the Roman Empire.

The subsequent conquest of Carthiginian Iberia gave Rome control over the highly productive mines in Spain which, alongside Carthage’s indemnity payments, meant a steady flow of silver became available.

As Kenneth Harl explains:

“In the Second Punic War, the Republic reforged it’s silver and bronze currency into a system of denominations that endured for the next 450 years. Rome also learned how to avoid massive default in a crisis by devaluing the silver coinage, adopting a fiduciary bronze currency and minting emergency gold coins. The Romans added these measures, well known to Greek states since the fifth century B.C., to their arsenal of financial expedients.”

In 141BC, the denarius was revalued from 10 asses to 16. Bronze asses had gradually wore down with heavy use and fell short of their original minted weight.

In order to prevent reminting a huge amount of bronze coinage the revaluation aligned the relative values at the market rate.

Julius Caesar’s Denarius

In 49BC, during the Civil War at the end of the Republic, Julius Caesar seized the state reserves.

He began to strike silver denarii bearing his name.

He also struck significant amounts of gold aureii.

The aureus was an 8g gold coin and in 46BC the exchange rate to the silver denarius was set at 25:1.

Caesar gradually transformed the coinage away from Republican icongraphy, replacing it, as Kenneth Harl describes, with:

“His titles and symbols of office, his ancestors and patroness Venus, and finally his own portrait.”

After his death in 44BC, Caesar’s image continued to adorn the denarius.

Octavian’s Denarius

Following the death of Julius Caesar, both Octavian (also known as Augustus) and Mark Antony minted their own denarii.

This was both to pay the bills and to lay claim to being Caesar’s heir.

When Octavian and Mark Antony united in the Second Triumvirate with Lepidus, they struck new denarii bearing their portraits.

In 23BC, after Octavian defeated Mark Antony in the Battle of Actium, he undertook a reform of the Roman coinage that would last almost two hundred years.

This reform established a new base metal currency for smaller denominations and set them in fixed exchange rates with denarii and aureii.

Kenneth Harl describes the reform:

“The keystone of this edifice was the denarius, the “link coin”, against which all other coins, including provincial and civic ones, could be reckoned and exchanged. For the first and last time in their history the peoples of the Mediterranean enjoyed, in the denarius, a common measure of value. Augustan coinage owed its success foremost to the economic growth stimulated by the Roman peace, but the coinage itself contributed to this growth by facilitating transactions, both large and small.”

The purity of the denarius had also, at times, fallen to as low as 92% during the latter years of the Republic. Octavian restored it to 98%.

Nero’s Denarius

Nero became the emperor of Rome in 54AD.

Nero’s budget was strained due to several factors that will not be unfamiliar to the modern reader:

- War debts

- Rebuilding costs after a disaster (the great fire of Rome)

- Extravagant imperial spending.

In 64AD he began debasing the denarius by reducing its silver content.

Reductions in the silver content of the denarius had been happening since its inception. But these tended to be small reductions and, when circumstances allowed, the silver content was restored to its original weight.

What began under Nero was a large scale debasement of the currency.

This continued over several hundred years and ultimately contributed to the fall of Rome.

The Romans had no bond market. So governments had no method of deficit financing. If there were no new inflows of gold and silver from conquest and the government was running a budget deficit, then debasing the currency became the easiest method.

What this meant was taking the coinage obtained from taxes and minting them into a new coin with a lower silver content but with the same face value. This enabled the emperor to increase the money supply.

Nero debased the denarius by 20%. For every 1 million denarii taken in taxes, he was able to issue 1.2 million new denarii.

These new coins were accepted by the Roman public only because of the long history of imperial coins as sound money. Kenneth Harl observes the irony:

“Ironically, public faith in imperial coins made possible the policies of debasement that eventually eroded the Augustan currency…Debasement netted Nero revenues, but it also courted risks. Price increases sparked by the debasement in 64 apparently had little long-term impact, but imperiling confidence in the currency was the first step toward financial disaster. The international reputation of Roman coins was tarnished.”

Trajan’s Denarius

Trajan (98 – 117AD) took an interesting approach. He minted denarii according to Nero’s weights but he restored earlier designs.

These went back as far as the late second century BC during the Roman Republic.

The aim was to improve public faith and confidence in the money by appealing to tradition, heritage and familiarity.

Kenneth Harl once again:

“Trajan, by restoring older designs, acknowledged the danger that debasement and recoinage could undermine this trust and trigger a panic.”

Yet within six months of issuing the new coins Trajan debased the denarius by another 3-4%.

Once a debasement starts, it is very hard to stop.

The Great Debasement of the Denarius

By the time Marcus Aurelius became emperor in 161AD the denarius had been debased 26.5% in the nearly 200 years since Nero.

Marcus Aurelius debased the denarius another 4%.

Kenneth Harl explains why the emperors did it:

“Although each debasement drove up wages and prices, the lag in these rises enabled the imperial government to net surplus revenues exceeding the short-term effects of inflation. During war, emperors found It dangerous not to debase.”

In 215 Caracalla introduced the antoninianus. This was a silver coin with a face value of double a denarius but only 80% of the silver content of two denarii.

Gresham’s law went into effect as the denarius was hoarded. People preferred to pay with the coin with a lower silver content (the antoninianus) and hold onto the one with the higher silver content (the denarius). Prices rose to reflect the reduced amount of silver in the coin.

Elagabalus (218-222AD), two emperors after Caracalla, recognised the danger and abandoned the antoninanus and the denarius re-entered circulation.

By the rule of Severus Alexander in 222-235AD the denarius contained only 40% of the silver content of Octavian’s denarius.

Up until 235AD, the public still retained confidence in the denarius. Price inflation was approximately equivalent to the rate of debasement. While this caused problems in the economy, at least citizens could be confident in what their money was worth.

After 235AD things changed.

The denarius was rapidly debased to fund the Roman war machine. Public confidence disappeared and an inflationary spiral began.

The emperors believed that the debasement was to fund a temporary military crisis and that in victory they would acquire a booty of gold and silver.

But this was no temporary crisis. This was the Crisis of the Third Century that nearly brought the downfall of Rome and lasted from 235 – 284AD.

In 238AD the antoninanus was revived. It too had been further debased, now with only 70% of the silver of two denarii.

Over the next several decades the antoninanus was rapidly debased and public confidence was destroyed.

Aurelian introduced a new silver coin, the aurelianianus, while Diocletian introduced the silver argentus nummus, intended to be a resurrection of Nero’s denarius. These coins never regained the status that the denarius once held.

Diocletian undertook a significant monetary reform to try and improve Rome’s finances after the Crisis.

But his most significant move was introducing a new gold coin, the solidus.

Gold rather than silver became the principal monetary standard and the glory days of the denarius were well and truly over.

Collecting Roman Denarii Today: Where To Buy?

There are plenty of denarii out there in the market for sale.

While not something you probably want to buy for the silver content, stick with silver bullion for that, there is something to be said for adding such a coin to your collection for historic and collectible purposes.

In the U.S. you can buy a denarius from APMEX and in the UK you can buy them from the Royal Mint.

Read More: How Much Is A Roman Denarius Worth Today?

5 Lessons From A Study Of The Roman Denarius

The story of the Roman denarius—from its rise as a stable silver coin to its gradual debasement and eventual fall—carries important lessons for investors and society today. Here are five key takeaways:

1. The Perils of Currency Debasement

The Roman government repeatedly reduced the silver content of the denarius to cover expenses, particularly military costs. This led to inflation, loss of trust, and economic instability.

Investors today should be wary of fiat currency depreciation due to money printing and inflation. Hard assets like gold, silver, and Bitcoin can serve as hedges against monetary debasement.

2. Short-Term Political Decisions Have Long-Term Economic Consequences

Roman emperors debased the denarius to fund short-term needs (wars, public works, and political favors), but this eroded confidence in the currency over time, contributing to economic decline.

Politicians today often make short-term economic decisions (such as excessive stimulus or debt monetization) that create long-term problems like inflation or financial instability. Investors should focus on long-term sustainability rather than short-term political narratives.

3. The Importance of Trust in Financial Systems

As the denarius lost its silver content, people hoarded older silver coins with more precious metal content, leading to a collapse of trust in the currency and trade disruptions.

Financial systems, ancient or modern, rely on trust. If people lose faith in central banks or government debt, they seek alternatives (Bitcoin, gold, commodities, or offshore investments). Investors should diversify to prepare for crises of confidence.

4. Inflation Disproportionately Harms the Middle and Lower Classes

As the denarius was debased, prices soared, wages lagged, and the wealth gap widened. The elites could protect their wealth through land and hard assets, while the poor suffered.

Inflation today benefits asset holders (real estate, stocks, commodities) but erodes the purchasing power of those dependent on wages. Investors should prioritize real assets and avoid being overly reliant on cash. Equally though, investors should be aware that while they may be able to protect themselves, inflation always and everywhere creates serious problems in society at large.

5. The Cycle of Monetary Collapse and Reset

The decline of the denarius mirrors many historical cases where fiat currencies collapse after prolonged mismanagement. Eventually, the Roman economy had to reset under new forms of money.

Investors should recognize the patterns of monetary cycles and be prepared for potential currency resets, financial system reforms, or shifts to new monetary standards (e.g., Bitcoin, CBDCs, or a return to commodity-based money).

Frequently Asked Questions

Its value fluctuated over time, but during the Roman Republic, a denarius could pay a soldier’s daily wage or buy several loaves of bread.

Originally, the denarius contained 95% silver, but over time, it was debased to as low as 2% silver by the 3rd century AD.

Emperors reduced the silver content to finance wars, pay off debts, and fund government expenses, leading to inflation.

The denarius gradually disappeared, replaced by gold coins like the solidus under Constantine.

The word “denarius” comes from the Latin “deni” (ten) because it was originally worth 10 bronze asses.

Yes! Ancient denarii are available through coin dealers, auction houses, and online marketplaces

The value of a Roman denarius today depends on factors like age, rarity, condition, and historical significance. Common denarii in decent condition typically sell for $100–$300, while rarer pieces, such as those from the reign of Julius Caesar or Augustus, can fetch $1,000 or more at auctions. Highly prized specimens in mint condition or with unique markings have been known to sell for $5,000+

Conclusion

The Roman monetary system was glorious while it lasted.

The use of precious metals as money contributed significantly to the economic stability and might of Rome.

At the center of it all was the Roman denarius.

It became the monetary standard in 211BC as a 4.5g coin with 95% fineness.

However, the great flaw in the denarius, and in precious metals as money generally, is the ability to debase the coins by reducing the precious metal content. This is far less of an issue than with fiat money, where new supply can be created very easily, but it was an issue nonetheless.

Rome succumbed to monetary debasement and inflation and this contributed to the fall of the empire.

The denarius’ story is a warning—economic mismanagement and currency debasement erode prosperity over time. For investors, the lesson is clear: hedge against inflation, prioritize real assets, and prepare for financial regime shifts.

I’ve leave you with a final word from Kenneth Harl:

“The success of Roman coins contributed in no small measure to the long periods of price and wage stability. Repeated use of the same denominations for the purchase of familiar units of goods bred public faith not so much in the abstract notion of Roman currency but rather in specific denominations such as the denarius, and it was this fact that enabled emperors to manipulate the currency during the third and fourth centuries.”

To your protection and prosperity,

Thomas

P.S. Have I left out anything important? Please let me know. Or if you found this information to be of high value, drop me a line, too. I love hearing from readers.

Sources

Harl, Kenneth W. Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. To A.D. 700. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Image Credits

137 BC Denarius is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5

211 BC Denarius is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5

Julius Caesar Denarius is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5

Octavian Denarius is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5

Nero Denarius is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5

Trajan Denarius is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0

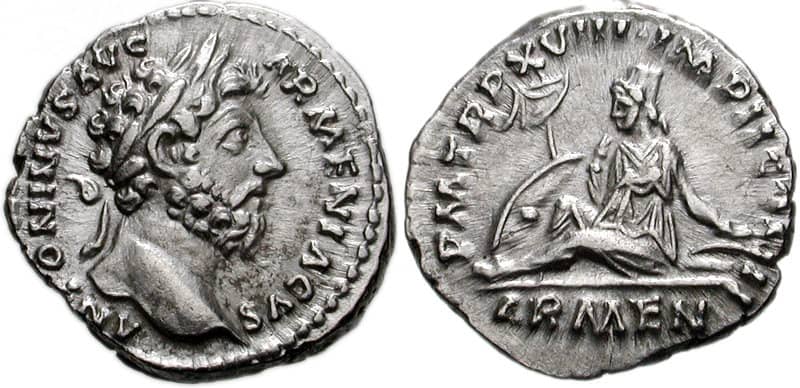

Marcus Aurelius Denarius is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Severus Alexander Denarius is in the public domain