Last Updated on April 22, 2025

There is a lot to learn from the inflation in Rome that ravaged the empire towards the end.

It is a cautionary tale and one that we can draw many insights from.

It’s quite natural that we might look at the story of the inflation in Rome and draw comparisons to our American dominated world and wonder whether a similar story will play out for us.

As Glen Bowersock wrote of the Roman Empire:

“We have been obsessed with the fall: it has been valued as an archetype for every perceived decline, and, hence, as a symbol for our own fears.”

There are parallels we can draw between the debasement of the Roman coinage and the debasement of modern fiat currencies.

Where along the curve are we?

Are we at the beginning, the middle or the end?

What are the consequences going to be for us?

Will we go down with civil war, economic chaos and foreign invasion and into a long period of civilizational decline, like the Romans?

Or will it be more like the recent example of the British Empire, where financial and military power recedes and yet the nation remains a significant player in the world?

Personally, I think we are still quite a long way from the end of the American Empire.

It only became the world’s dominant power in World War Two, so it is still quite young historically.

I wouldn’t bet the farm on a total collapse just yet.

Yet regardless of where we are on the curve, there is still a lot that can be learned from the inflation in Ancient Rome. This insight can help you navigate this current period of economic uncertainty.

The History of Ancient Rome is long and detailed, spanning over 1200 years from the emergence of the city to the fall of the Western Empire. Yet you don’t have to know every fact and detail to gain an appreciation of the basics.

This is an abridged and easily digestible version of the story of Rome, the role of inflation in its collapse and the lessons today’s investors can learn.

A Brief History Of Money In Ancient Rome

Money In The Roman Republic

Tradition teaches that Rome was founded in 753BC. It was initially a monarchy.

This lasted until 509BC when a political revolution overthrew the king and a republic was installed.

In the early years of the Roman Republic bronze coins called aes were used.

Later in the Republic, from 211BC, the silver denarius became the dominant form of money. When it was first minted the denarius contained about 4.5 grams of silver and the coin had over 95% of the precious metal.

The word denarius meant 10 asses although it was later revalued to 16 bronze asses around 140BC.

Gold coins were minted occasionally but rarely. Silver dominated but bronze continued to be used as well.

Julius Caesar, the last leader of the Roman Republic, who ruled as a dictator from 49BC to 44BC started minting gold coins in larger quantity and standardised the weight.

Caesar’s gold aureus contained a little over 8 grams of gold and was worth 25 denarii.

Caesar emerged during a period of instability, however his monetary reform did a lot to bring about a period of economic stability that lasted after his death and into the early years of the Roman Empire.

What Caused Inflation In The Roman Empire?

Julius Caesar was assassinated by his political opponents in 44BC. A period of turmoil and civil war followed until Octavian emerged as the first Roman Emperor in 27BC.

Stability lasted from Octavian’s emergence until the reign of Emperor Nero who took power in 54AD.

Nero was the first emperor to engage in what is known as coin clipping. The emperor would recall the coins then mint them into a new coin with a lower metallic content but with the same face value.

Without any means of deficit financing, when government expenditure rose, coin clipping was the easiest method for emperors to raise revenue.

This was currency debasement, pure and simple, and was inflationary.

Initially this inflation was very mild. While the debasement continued under a number of emperors, during the early period the inflation rate in the Roman Empire was less then half a percent per annum.

In 235 AD Emperor Severus Alexander was assassinated and a period known as the Crisis of the Third Century began. This was a period of political disorder and military entanglements, which also brought about an increase in government spending and further debasement of the currency.

Each currency debasement provided the emperor some temporary relief. But the citizens would soon get angry with rising prices, which would often lead to price controls. This would then lead to further debasements and price rises in a vicious cycle.

Since price controls prevented prices from rising to meet a market equilibrium, it become unprofitable for many goods to be produced. This then triggered an economic decline and caused prices to rise both because of currency debasement and because of shortages.

How Did Diocletian and Constantine Try To Fight Inflation?

The Crisis of the Third Century came to an end in 284 AD as Diocletian took power. While he was able to end the political chaos and restore order, he could not entirely solve the economic problems.

Diocletian introduced the gold solidus to replace the old aureus, with the new coin containing 5.5 grams of gold. This was significantly less than the slightly over 8g in the aureus.

This was an attempt to stabilise the economy, however Diocletian only issued the solidus in small quantities and it did not stop runaway inflation.

With inflation still ravaging the economy Diocletian turned to further price controls with his famous Edict on Maximum Prices. This was issued to try to restore order to the economy of Rome but it ended up being counter-productive as the price ceilings were far too low.

Many producers could not make a profit at such low prices and went out of business. This led to further shortages and put even more upward pressure on prices.

It was Diocletian’s successor Constantine who managed to restore stability through monetary reform.

Constantine issued the gold solidus in 312AD at a weight of 4.55 grams. This was done in very large quantities and permanently replaced the aureus.

The solidus was worth 275,000 debased denarii, which by that time had seen their precious metal content fall from 95% to around 5%. Remember when Julius Caesar issued the aureus it was equivalent to 25 denarii.

Constantine maintained the fixed weight of the solidus without debasement and this managed to restore some stability to the economy of Rome.

In fact the solidus was so successful that it outlasted the Western Roman Empire and was used as the currency of the Byzantine or Eastern Roman Empire for many centuries after the fall of Rome.

Unfortunately, the monetary reform of Constantine, while somewhat effective in the short term, was not enough to prevent the continuing decline of Rome in the long term.

After a series of attacks and incursions by foreign invaders, mainly Germanic tribes, Rome finally fell in 476 AD when the last emperor Romulus Augustulus was deposed by the Barbarian Odoacer.

How Inflation Contributed To The Fall Of Ancient Rome

The exact causes of the collapse of the Roman Empire are widely debated among historians, with economic and monetary causes being a key part of the debate.

I’ll turn to Ludwig von Mises for an explanation who weigh in on the debate in his classic work Human Action. Mises argues that the Roman Empire fell because it did not adopt the spirit of liberalism and free enterprise. Instead emperors resorted to coercive action which undermined the financial and military power of the government.

Mises abstains from debating whether Ancient Rome was a capitalist system or not. But he acknowledges that at its peak it:

“Reached a high stage of the social division of labor and of interregional commerce.”

What fueled the expansion of Rome was military conquest and one of the primary concerns of the emperor was how to pay the troops.

One of the easier ways to do this was to acquire new sources of precious metals in their conquests along with other forms of wealth like slaves.

David Orrell calls this the military-financial complex:

“The Greek and Roman Empires were both built on a military–financial complex that obtained bullion and slaves from conquered lands, paid soldiers using the minted coins, and collected taxes in said coins. Money was therefore a tool to

transfer resources from the general population to the well-armed state.”

During Rome’s ascent, the need to debase the coinage was avoided due to new supplies of precious metals flowing in from both Roman mines and foreign conquests.

As Rome conquered more and more of the known world they ran out of new territory to acquire. The supply of easily obtainable bullion dried up and as political disorder grew the output of local mines was reduced. Debasement became an easier option.

The military-financial complex is another one of the reasons that emperors were tempted into debasement. In particular Septimus Severus’ debasement was due to the need to increase the size of the army in order to preserve his political position.

As the number of soldiers in the army increased the government needed more money to pay wages. Yet paying in debased coins drove up prices, which in turn caused the soldiers to demand a higher wage.

The injection of debased coins into the economy did not increase prosperity and just made everyone poorer. This inflation, combined with increasing taxes, price controls and military crises meant trade declined.

This did not happen immediately all at once, but was a process that took place over a long period of time. It was initially slow and gradual but sped up over time.

The interconnectedness of trade in the wider empire suffered as more and more economic activity took place on the local level. Many fled the cities and relocated in rural areas.

Mises points out that inflation and price controls led to shortages of grain in the cities. Large land owners ceased producing supplies for the cities and became a more self-sufficient local unit.

Instead of large scale farming the large estate holder became a landlord collecting rents from tenants or sharecroppers, who were refugees who had fled the cities.

Mises explains:

“A tendency toward the establishment of autarky of each landlord’s estate emerged. The economic function of the cities, of commerce, trade, and urban handicrafts, shrank. Italy and the provinces of the empire returned to a less advanced state of the social division of labor. The highly developed economic structure of ancient civilization retrograded to what is now known as the manorial organization of the Middle Ages.”

Mises argues therefore that Rome collapsed from within rather than because of the foreign invaders, who merely took advantage of the weakness that Rome inflicted on itself.

“What brought about the decline of the empire and the decay of its civilization was the disintegration of this economic interconnectedness, not the barbarian invasions. The alien aggressors merely took advantage of an opportunity which the internal weakness of the empire offered to them. From a military point of view the tribes which invaded the empire in the fourth and fifth centuries were not more formidable than the armies which the legions had easily defeated in earlier times. But the empire had changed. Its economic and social structure was already medieval.”

Lessons From The Inflation In Rome

1. Collapse is a Long Drawn Out Process

Nero, the first coin clipper, assumed power in 54AD. While Rome did look pretty shaky during the Crisis of the Third Century she recovered her footing, eventually falling in 476AD.

That is over 400 years from Nero to final collapse. It was a long time.

Unless you are deeply familiar with the history of Ancient Rome, it can be a little difficult at first to wrap your head around how long their history was.

Collapse can take a long time. It’s not all Weimar style. We don’t know where we are on that curve of collapse and we won’t know until we have hindsight. Right now we can only speculate.

But as sure as night follows day, we know that the American Empire will collapse one day as all empires inevitably do. Whether that is this decade or even this century remains to be seen.

We can probably say that American Empire began in 1898 under William McKinley in the Spanish American War. But it did not fully ascend to become the world’s dominant power until World War Two, when the baton passed from Britain to America.

In financial terms the first big moment of debasement came with FDR in the 1930s, which was then followed by Nixon in the 1970s.

If you compare this to Rome, it is still very early days.

So I wouldn’t bet too much on a dollar collapse or a rapid decline in American power. You might be right in principle but you might get the timing very wrong.

An investor’s lifetime is short compared to the lifetime of a state. It’s good to think long term, but not too long.

If you load up too much on inflation hedges now because you are predicting a demise in the monetary system, you may give up a lot of potential gains if it doesn’t happen for several decades. It is good to be defensively prepared but it is possible to overdo it.

2. The Natural Tendency of Government is Debasement

Governments act in their own interests. Their number one priority is their own survival. Long term financial stability should therefore be very important to them.

However in numerous examples throughout history, you can see governments acting in a short sighted way and trading away long term stability for the short term benefits they get from debasing the currency.

It either comes from ignorance, desperation or a willingness to kick the can down the road. But it is entirely normal behaviour from governments. I don’t endorse it but I expect it. It does frustrate me but I’ve learned that it is better to accept it and channel my energies into protecting myself rather than getting too annoyed at monetary policy. I’d rather enjoy life.

History also shows that it is very hard for governments to stop the debasement once they start. It requires enormous political courage to do so. That’s why we have seen reserve banks governors get themselves into such a pickle over recent years. They unleashed quantitative easing and have found it incredibly difficult to normalise monetary policy.

Constantine is an example of a politician who did have the courage to enact serious monetary reform and that is one of the reasons why I find him so fascinating. But even then, a lot of damage had already been done and Constantine’s actions did not prevent the empire from falling in the end.

The message here is don’t waste energy getting frustrated at the government or the Fed. Instead take the time to understand what they are doing, why they are struggling, what the likely outcome is and protect yourself accordingly.

3. Be Prepared For A Constantine

Mainstream financial commentators see nothing wrong with the picture when they look at the levels of sovereign debt and central bank balance sheets.

Clearly they are deluded.

Some commentators who understand Austrian Economics and genuinely see the problem think there is no way out of this except through the destruction of the dollar.

This is a maybe.

Another alternative is that some time in the future a politician emerges who genuinely gets their act together and enacts serious monetary reform.

As Jim Rickards explains this wouldn’t actually be that hard. They just have to remonetise gold and set the price appropriately according to the expansion of the money supply. Rickards suggests $10,000.

Taking the US off the shadow gold standard, where gold is merely a reserve asset, and putting her back onto an actual gold standard would be akin to Constantine committing to maintaining the metal weight of the solidus.

It could happen.

So again, don’t bet too much on a collapse. Be prepared for any eventuality.

4. The State is Unlikely to Relinquish Its Monetary Monopoly Easily

A state’s sovereignty is defined by two monopolies. A monopoly on the use of force and a monopoly on the control of money and taxation within a given geographic territory.

It has always been this way.

Some states have tried to go further and mandate adherence to the state religion or the cult of personality of the leader. However, even the most totalitarian have never been able to completely achieve this because to do so would require thought control, which is not possible. There will always be dissenters.

Money and military force are much more easily controlled.

A government’s primary way of mandating the use of their money is through taxation. If you have to pay taxes in a certain form of money and that creates a demand for it. This was true in Roman times and it is still true now.

They can create legal tender laws and can also restrict other money throughout outright ban e.g. what FDR did to gold, or by declaring it an investment upon which capital gains are due e.g. how most governments treat Bitcoin.

Part of the idealism behind cryptocurrency, especially Bitcoin and Monero, is that it will create a separation of money and state. The hope is that governments either voluntarily give up their monopoly power of money and allow the free market to step in or that governments will reluctantly give up their monetary power when the current fiat currencies collapse.

I am a realist, not an idealist.

I do not see a situation where governments will easily give up monopoly power over issuing money.

I believe Bitcoin is the hardest form of money in human history. I would love to see it emerge as the world’s money.

But the realist in me says I don’t think that will matter to the state and they will fight tooth and nail against it and to maintain their control over money.

When governments debase a currency too much they normally just issue a new one. This is what Constantine did. This is what Weimar Germany did.

When the world’s fiat currencies go under, I think the state will try to find its own solution and I don’t think that solution will be Bitcoin, as much as I might wish it were.

Like Constantine did that solution might be gold, which is hard money governments can control more easily. Or it might be the IMF’s SDRs. Or it might be a new fiat currency life CBDCs.

Of course there is a possibility that widespread Bitcoin adoption and non-compliance with government money could force the state out of the money issuing business, like what happened in the Ming Dynasty in China. Or, like El Salvador, the state decides if will adopt Bitcoin itself.

History has shown that when government money fails, as it always does eventually, governments sometimes reluctantly accept the circulation of whatever form of money the market determines to be superior.

So while it’s possible, if Bitcoin succeeds if separating money from the state this would be a rare event in world history. If it was global and permanent, it would be unprecedented.

Call me pessimistic, and trust me I will be glad to be wrong, but I just don’t see it as being very likely, at least not in the short to medium term, the governments will relinquish their monetary power easily.

5. Precious Metals Are Not 100% Effective As Money

While precious metals were the hardest money we had until the emergence of Bitcoin, the Roman story clearly shows their flaws.

Coin clipping shows that you can have precious metals as government money but it can still be abused.

Gold and silver coinage, if controlled by a state, is not 100% effective as money for this reason. Neither was the classical gold standard as governments still had a small, albeit limited, ability to manipulate their money supply. And they just abandoned it when it didn’t suit them anymore.

Yet regardless of their flaws, gold and silver money is still preferable to fiat.

In Roman times the precious metals retained their purchasing power when you considered the weight of the metal rather than the face value of the debased coin.

1 oz of gold in the time of Julius Caesar would buy you more or less a similar amount as 1 oz of gold would in the time of Constantine. 1 oz of gold would also buy you more or less a similar amount today.

This is instructive because it shows us that in the ancient world, just as much as in the modern world, precious metals retain purchasing power. That is their primary attraction.

Of course, gold has not performed as well as Bitcoin in recent years, which has benefited from the speculative rise in value due to its increasing adoption. But if you look at the long term price of gold going back to the 1970s, you can see that it has fulfilled its wealth preserving role extremely well.

Conclusion

Rome rose to power through sound money, strong trade networks and military conquests to become the most powerful empire of the Ancient World.

There is a natural fascination with Ancient Rome because there are so many insights about our own society that we can gain from studying theirs.

In particular how they debased their money, destroyed their economy and were internally weakened to the point they succumbed to foreign invaders.

The lesson for us as a society is to maintain sound money. Since this will certainly be ignored by governments, the lesson for you as an individual is to protect yourself from debasement of the currency by owning hard assets that will preserve their purchasing power over time.

While you shouldn’t necessarily count on an imminent collapse you should prepare for a gradual debasement of the currency.

Sources

Ammous, Saifedean. The Bitcoin Standard : The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2018.

Boatwright, Mary T, Daniel J Gargola, Noel Lenski, and Richard J A Talbert. The Romans : From Village to Empire: A History of Rome from Earliest Times to the End of the Western Empire. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Bowersock, Glen W. “The Vanishing Paradigm of the Fall of Rome.” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 49, no. 8 (1996): 29–43.

Gibbon, Edward. Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,. S.L.: Forgotten Books, 2017.

Rickards, James. The New Case for Gold. London: Penguin Business, 2019.

Image Credits

The Colosseum by Yoal Desurmont on Unsplash

Fori Imperiali by Massimo Virgilio on Unsplash

Roman Denarius is in the public domain {{PD-US}}

Solidus is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

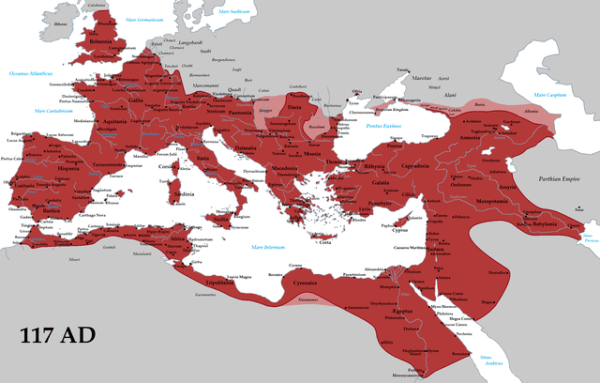

Roman Empire is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0